Fifth Sunday of Ordinary Time

Scripture Readings: Is. 58:7-10; I Cor. 2:1-5; Mt. 5: 13-16

About sixty years ago, Arthur Miller wrote a play, Death of a Salesman, which has remained a classic ever since. It is the story of a man who seemingly lost his soul in pursuit of an empty dream of recognition and success through becoming a “great” salesman. One of his sons describes it as “riding on a smile and a shoeshine.” Any possible success depends totally on the desires and whims of those who are buying what you are selling. Another son says that “he didn’t know himself.” Finally, betrayed by the system to which he sold himself (he was fired), he commits suicide.

About sixty years ago, Arthur Miller wrote a play, Death of a Salesman, which has remained a classic ever since. It is the story of a man who seemingly lost his soul in pursuit of an empty dream of recognition and success through becoming a “great” salesman. One of his sons describes it as “riding on a smile and a shoeshine.” Any possible success depends totally on the desires and whims of those who are buying what you are selling. Another son says that “he didn’t know himself.” Finally, betrayed by the system to which he sold himself (he was fired), he commits suicide.

The play seems to capture the slow death to the person that enthrallment to a market society, a society ruled by what Pope Francis has called the scientific-technocratic paradigm, can inflict. The insight the play presents has not ceased to be relevant and revealing. We are in a society that values the impersonal, smooth transactions which speed getting the job done. We cultivate the split between what is personal and what is public, between what is interior and what is exterior. Minimal exposure and involvement facilitate opportune investment or withdrawal. Arthur Miller’s Willy Loman had ignored and betrayed his own soul in pursuit of a glory which evaporated in the light of reality.

The Gospel constantly critiques the illusion of separating what is personal and interior from what is public, communal, and external. It insists on the need to integrate and unify all the realms of our being. When the Lord says you are the salt of the earth and you are the light of the world, he is not congratulating us for being head and shoulders above others. You are Number One. You are the Cream of the Crop. We can hear this in a way which seems to raise us above and separate us from “the world.” You are a chosen nation, a people set apart. We seem to have won some spiritual lottery which excludes us from serious concern in the future. Or perhaps it just sounds like empty bombast, rhetorical encouragement a coach might give his last-place team before that play against the first-place team.

The Gospel constantly critiques the illusion of separating what is personal and interior from what is public, communal, and external. It insists on the need to integrate and unify all the realms of our being. When the Lord says you are the salt of the earth and you are the light of the world, he is not congratulating us for being head and shoulders above others. You are Number One. You are the Cream of the Crop. We can hear this in a way which seems to raise us above and separate us from “the world.” You are a chosen nation, a people set apart. We seem to have won some spiritual lottery which excludes us from serious concern in the future. Or perhaps it just sounds like empty bombast, rhetorical encouragement a coach might give his last-place team before that play against the first-place team.

This is not descriptive speech, giving us information about our place in the world. Perhaps we could call it declarative speech: speech which brings into being what it says. It is creative speech which brings into being something out of nothing. It is the kind of speech which creates a new relationship between the speaker and those spoken to. It is the kind of speech we hear when someone says I really need your help or I love you or you can count on me to be with you or let there be light or this is my body. They are words of consecration, endowing us with a new power but not removing us from the contexts in which we live. We are to be salt of the earth, for the earth. Light of the world and for the world. This kind of speech does not need eloquence, sublimity of words or wisdom. We are not selling anything. These words are a demonstration of Spirit and power. Our faith rests on them. Our faith is performative (as Pope Benedict XVI has said): it realizes itself as it moves and acts in the world in trust and hope.

It is Christ who is salt and light and it is by our relationship to him that we become salt and light for others. Salt and light seem common and prosaic. They are indeed common and universal; prosaic, they are not. Life is indispensable without the subtle and pervasive operations of these agents which do not draw attention to themselves. They enable the creative potentialities of whatever it is that they meet. Salt was used as a fertilizer, as a preservative, and as a hidden, mysterious transformer which can excite our taste. Without light we cannot see, distinguish differences, or change the external world into nurturance through photosynthesis. Manifold, subtle, agile, clear, unstained, certain, not harmful, loving the good …Wisdom is mobile beyond all motion and she penetrates and pervades all things (Wisdom 7:23-24). Salt is a symbol for wisdom, for a taste of the things of God. Salt and light are content to be unobtrusive and known by their effects. Let your light shine before others that they may see your good deeds and glorify your heavenly Father. God is known through his effects, the power of God at work in us. Salt and light which seek the dream and illusion of glory redounding to themselves are good for nothing: salt which is insipid and light under a bushel—frustrating the purpose and mission and power they had been given.

It is Christ who is salt and light and it is by our relationship to him that we become salt and light for others. Salt and light seem common and prosaic. They are indeed common and universal; prosaic, they are not. Life is indispensable without the subtle and pervasive operations of these agents which do not draw attention to themselves. They enable the creative potentialities of whatever it is that they meet. Salt was used as a fertilizer, as a preservative, and as a hidden, mysterious transformer which can excite our taste. Without light we cannot see, distinguish differences, or change the external world into nurturance through photosynthesis. Manifold, subtle, agile, clear, unstained, certain, not harmful, loving the good …Wisdom is mobile beyond all motion and she penetrates and pervades all things (Wisdom 7:23-24). Salt is a symbol for wisdom, for a taste of the things of God. Salt and light are content to be unobtrusive and known by their effects. Let your light shine before others that they may see your good deeds and glorify your heavenly Father. God is known through his effects, the power of God at work in us. Salt and light which seek the dream and illusion of glory redounding to themselves are good for nothing: salt which is insipid and light under a bushel—frustrating the purpose and mission and power they had been given.

In a recent (January) address to the participants of a plenary meeting of leaders of the Institutes of Consecrated Life, Pope Francis reminded them that when someone does not find support for their vocation within their community, they will look for it outside. All of us need adequate help for the human, spiritual, and vocational moment we are living, i.e., spiritual accompaniment. The freshness and novelty of the centrality of Jesus, he said, must be maintained. When we assess the communities and world we live in, we must look hard at the way we have been salt and light. At the freshness, joy and hope we live from. At the way God has been manifest and operative in our deeds.

In a recent (January) address to the participants of a plenary meeting of leaders of the Institutes of Consecrated Life, Pope Francis reminded them that when someone does not find support for their vocation within their community, they will look for it outside. All of us need adequate help for the human, spiritual, and vocational moment we are living, i.e., spiritual accompaniment. The freshness and novelty of the centrality of Jesus, he said, must be maintained. When we assess the communities and world we live in, we must look hard at the way we have been salt and light. At the freshness, joy and hope we live from. At the way God has been manifest and operative in our deeds.

Fifth Sunday of Ordinary Time

[Scripture Readings: Job 7:1-4, 6-7; 1 Cor 9:16-19, 22-23; Mk 1:29-39 ]

In the Book of Job, the Lord asks Satan, “Where have you come from?” The devil replies, “[I have been] going to and fro on the earth, walking up and down on it.” One of our Abbot Generals who had to travel to and fro among many monasteries, said Satan should be an abbot. Our former abbot, Fr. Brendan, was away from the monastery so much that his sister said, “Next time my brother is visiting New Melleray tell him I said hello.” And now our new abbot, Fr. Mark, has even more responsibilities for other communities than Fr. Brendan had. So, we're fortunate to have Fr. Mark with us this morning. But all that traveling is necessary. Abbots are doing the right things for the right reasons when they hit the road.

In the Book of Job, the Lord asks Satan, “Where have you come from?” The devil replies, “[I have been] going to and fro on the earth, walking up and down on it.” One of our Abbot Generals who had to travel to and fro among many monasteries, said Satan should be an abbot. Our former abbot, Fr. Brendan, was away from the monastery so much that his sister said, “Next time my brother is visiting New Melleray tell him I said hello.” And now our new abbot, Fr. Mark, has even more responsibilities for other communities than Fr. Brendan had. So, we're fortunate to have Fr. Mark with us this morning. But all that traveling is necessary. Abbots are doing the right things for the right reasons when they hit the road.

Jesus traveled a lot, too. In today's Gospel we heard that Jesus went throughout the whole of Galilee, going from village to village, preaching, healing the sick, and driving out demons. Don't we all have a few demons that we wish the Lord would cast out of our hearts? Think of the eight capital sins: pride, vainglory, avarice, sloth, lust, dejection, gluttony and anger.

Let's focus on two of them: vainglory and pride. Sr. Mary Margaret Funk in her book1 on the eight capital sins, teaches that vainglory is doing the right things but for the wrong reasons, and pride is doing the wrong things for the wrong reasons.

Let's focus on two of them: vainglory and pride. Sr. Mary Margaret Funk in her book1 on the eight capital sins, teaches that vainglory is doing the right things but for the wrong reasons, and pride is doing the wrong things for the wrong reasons.

Vainglory does the right things, like fasting, almsgiving, and prayer—for the wrong reason—to be praised. Fasting is a good thing, but not if it is done just to be seen by others.

St. Aelred2 reproaches monks and nuns who have left riches, status, nobility, and honors by entering the contemplative way of life, who now want to be called to council meetings and be given a role to play in the abbot's decisions. They become angry or hurt if something is done without their advice.

Pride is worse. It is doing the wrong things for the wrong reasons, like neglecting one's spouse or children, or murmuring about someone in community, or bragging about oneself, all out of self-centeredness.

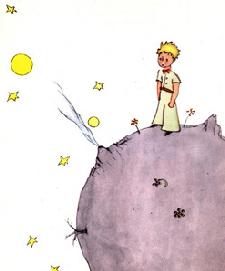

Do you remember the delightful story of The Little Prince?3 The boy approaches a small planet, an asteroid, inhabited by one person, a conceited man who says, “Ah! I am about to receive a visit from an admirer.” The little prince greets him, “Good morning. What a strange hat you're wearing.” The man replies, “It is a hat to raise when people acclaim me. Now, clap your hands.” The little prince claps his hands and the conceited man raises his hat in modest salute. So the little prince does it again, and the man raises his hat again, saying, “Do you really admire me very much?” “What does admire mean,” says the little prince. “To admire means you regard me as the most handsome, best dressed, richest, and most intelligent man on this planet.” The little prince replies, “But you are the only person on this planet.” “Admire me just the same,” he says. The little prince claps his hands, shrugs his shoulders and goes away saying, “Grown-ups are certainly very odd.” The conceited man continues glowing with pride, and looking for another admirer.

Do you remember the delightful story of The Little Prince?3 The boy approaches a small planet, an asteroid, inhabited by one person, a conceited man who says, “Ah! I am about to receive a visit from an admirer.” The little prince greets him, “Good morning. What a strange hat you're wearing.” The man replies, “It is a hat to raise when people acclaim me. Now, clap your hands.” The little prince claps his hands and the conceited man raises his hat in modest salute. So the little prince does it again, and the man raises his hat again, saying, “Do you really admire me very much?” “What does admire mean,” says the little prince. “To admire means you regard me as the most handsome, best dressed, richest, and most intelligent man on this planet.” The little prince replies, “But you are the only person on this planet.” “Admire me just the same,” he says. The little prince claps his hands, shrugs his shoulders and goes away saying, “Grown-ups are certainly very odd.” The conceited man continues glowing with pride, and looking for another admirer.

But pride is not always gloating about one's own excellence. Sometimes it is shame about one's own defects or limitations. There was a young boy named Joseph Lahey4 who injured himself in a sled ride at the age of four. He suffered a spinal injury that left him with a large hump on his back. He was too ashamed to undress in front of anyone, not for showers, or swimming, or sports. He always tried to hide himself, to withdraw. But now he had to undress for a medical exam. The doctor was a Christian and a very kind man. When he saw the hump he asked the boy, “Do you believe in God?” “Yes,” Joseph replied. “That's good,” the doctor said, “because God has blessed you with great beauty, be thankful.” The doctor filled out his report and stepped out of the room for awhile, as doctors do.  Joseph looked at the open report and in the space provided for “Physical Characteristics” he saw that the doctor had written, “Joseph has a beautiful face and a wonderful smile. He's a very lovable boy.” There was nothing at all about the hump on his back. That day Joseph's basic disposition changed to one of grateful love. His face became like a lamp radiating happiness and God's love instead of shame and self-depreciation.

Joseph looked at the open report and in the space provided for “Physical Characteristics” he saw that the doctor had written, “Joseph has a beautiful face and a wonderful smile. He's a very lovable boy.” There was nothing at all about the hump on his back. That day Joseph's basic disposition changed to one of grateful love. His face became like a lamp radiating happiness and God's love instead of shame and self-depreciation.

The demon of pride was cast out of Joseph by a good doctor who spread Christ's love around him. There are people like Job for whom “life on earth is a drudgery, filled with months of misery and troubled nights,” who say to themselves “I shall not see happiness again.” The vocation of every Christian is to help cast out those demons by bringing the love of Christ to those who live in misery. Because Christ wants us to have all that is true, good and beautiful forever.5 That's why Jesus went throughout the whole of Galilee, going from village to village, preaching, healing the sick, and driving out demons.

Fifth Sunday of Ordinary Time

[Scripture Readings: Is 6:1-2a, 3-8; 1 Cor 15:1-11; Lk 5:1-11]

So, what is it like to be a Christian… on the inside? Today we are told that it is like hearing and responding to a call. The readings of the last three Sunday's have been Call stories. The first three weeks of Ordinary Time we heard Jesus' Call story. Last week we heard Jeremiah's and this week that of Isaiah.

So, what is it like to be a Christian… on the inside? Today we are told that it is like hearing and responding to a call. The readings of the last three Sunday's have been Call stories. The first three weeks of Ordinary Time we heard Jesus' Call story. Last week we heard Jeremiah's and this week that of Isaiah.

Today we also hear the call of the first disciples. It is rather unusual because Jesus doesn't just say “Follow me.” Instead, he asks them to take a risk… on the inside. He gradually calls them from the safety of the land to going a short way out on the water. There he teaches them the Word of God. It is within the context of that Word that they are to view their interior risk. Then he tells them to go out to still deeper water and to increase their risk by dropping their nets, which they already know will not work. It does work and they know that all they did was obey. It was their ego's, their pride, that they risked. As a result, they learn something important here: they experienced success where they had already failed and it came from the Lord and their obedience to him. In short, what is important in this story is not what they do, but what is done to them… on the inside.

A Call comes from a specific person and is directed to a specific person; it is directed to her heart. On the inside a Call is experienced much like a conversion. We recently celebrated the conversion of St. Paul. Conversion happened to him. And there are elements of that which are similar to today's call… and to our call. Something happened to us.

First there is failure: Paul knocked to the ground; the disciples catch nothing. There is a falling short of the chosen ideal or disillusionment or dissatisfaction with life as we have been living it.

Then, the person is called by name. This means she is called by her total life experience, by her old world-view, her old ways of being affected. These have failed her. All things now will be new.

Finally, she is given a mission. It is an impossible mission. It is to live out the beatitudes.

So today this is what Luke is telling us it is like to be a Christian on the inside: it is to acknowledge failure of our old ways and to actually be attracted to an impossible mission to which we want to devote our lives.

But this is the crazy part: the call is more important than the person who gets it… and she knows it…on the inside.

Like the disciples, life as we had been living it was turned upside down when we encountered the person of Jesus of Nazareth. To say “something happened to them” is to say that He affected them. They left everything. That means they made a decision… and an irrevocable commitment.

This is what happened to us and this is what we have done. This is what the Church requires of us because it believes we are capable of it. Everyone here, married or professed religious, has made an irrevocable commitment. They made it in response to a call. Most of all, the call is more important than the person.

This must be experienced as true if one is to make and keep an irrevocable commitment.

Why?

We came to the monastery from a culture that believes no decision need be permanent. We even have removable scotch tape! Rarely is a decision of permanence, and thus of importance, asked of us. The Church has become unique in asking this of marriage, religious life, and the ordained. One of the reasons for this reticence to commit is that our desires may change; desire starts a search for its fulfillment. When the Call is most important it sparks and beckons desire. The Call and its desire, if we surrender to it, serves an ordering function on our daily lives and streamlines our choices so that they contribute to our search rather than impede it. Everything is evaluated according to its usefulness to answering the Call. And that makes commitment a good idea.

One's self-understanding forms the stable foundation for a decision that will hold sway over the rest of one's life. This self-understanding goes back to the beginning of the conversion experience: it is the experience of failure or dissatisfaction with life as we have been living it. We know we are called by name when we find ourselves reviewing our life, our history of decision-making, in the light of this Call. This experience makes us open to Grace. From the day we profess our vows one truth is clear: that no decision can be successful if it conflicts with the course we have freely set for our lives by our vows. Success in life depends on thorough fidelity to this truth about oneself. Taking on this obligation will rely on two things that happen to us and that must deeply affect us: this truth one knows about self and openness to the grace that will give the strength to live out this truth. That is where we risk our egos: we rely on Grace, rather than self. This is where we must “keep it simple.” The one truth finds its expression in one decision. This is because the one truth is more important than self.

One's self-understanding forms the stable foundation for a decision that will hold sway over the rest of one's life. This self-understanding goes back to the beginning of the conversion experience: it is the experience of failure or dissatisfaction with life as we have been living it. We know we are called by name when we find ourselves reviewing our life, our history of decision-making, in the light of this Call. This experience makes us open to Grace. From the day we profess our vows one truth is clear: that no decision can be successful if it conflicts with the course we have freely set for our lives by our vows. Success in life depends on thorough fidelity to this truth about oneself. Taking on this obligation will rely on two things that happen to us and that must deeply affect us: this truth one knows about self and openness to the grace that will give the strength to live out this truth. That is where we risk our egos: we rely on Grace, rather than self. This is where we must “keep it simple.” The one truth finds its expression in one decision. This is because the one truth is more important than self.

Each of us has a scripture or other inspiring verse that seems to sum up this one truth for us. We often put it on our profession card. St. Benedict gives us the simple rule-of-thumb that guided his life decision; it is one that unites us as Cistercians: “Prefer nothing whatever to Christ.”

…and that's what it's like…

Fifth Sunday of Ordinary Time

[Scripture Readings: Is 58:7-10; 1 Cor 2:1-5; Mt 5:13-16]

“You are the light of the world.” Reading these words of Jesus, while preparing this homily, I had a flashback — an image of myself at about age sixteen, and a member of the guitar mass at St. Martin de Porres parish in Warren, Michigan. I saw myself banging on my six-string guitar, singing a hymn, that was topping the charts in 1972: “We are the Light of the World!” At age sixteen, I don’t recall giving much thought to the words we were singing. We were having so much fun! It was Sunday morning. I was with all my cool friends, standing up in front of a few hundred people, making beautiful music. We thought we might actually be the light of the world. In those days, the adults were treating us teenagers as if we were pioneers, and we liked that. We felt like pioneers—introducing something completely new into the ancient Catholic church. It felt radical, and it was easy. It cost us nothing. We were revolutionaries and it was fun, we were enjoying ourselves. Ms. Grobelski, who had been complaining for weeks to the pastor about all that “hootenanny” going on at the 10:00 mass was sitting in the third row scowling—and we were enjoying that too. Nothing could dampen our spirits. We were the light of the world.

“You are the light of the world.” Reading these words of Jesus, while preparing this homily, I had a flashback — an image of myself at about age sixteen, and a member of the guitar mass at St. Martin de Porres parish in Warren, Michigan. I saw myself banging on my six-string guitar, singing a hymn, that was topping the charts in 1972: “We are the Light of the World!” At age sixteen, I don’t recall giving much thought to the words we were singing. We were having so much fun! It was Sunday morning. I was with all my cool friends, standing up in front of a few hundred people, making beautiful music. We thought we might actually be the light of the world. In those days, the adults were treating us teenagers as if we were pioneers, and we liked that. We felt like pioneers—introducing something completely new into the ancient Catholic church. It felt radical, and it was easy. It cost us nothing. We were revolutionaries and it was fun, we were enjoying ourselves. Ms. Grobelski, who had been complaining for weeks to the pastor about all that “hootenanny” going on at the 10:00 mass was sitting in the third row scowling—and we were enjoying that too. Nothing could dampen our spirits. We were the light of the world.

It wasn’t till many years later, that I came across an article in the Catholic journal “Communio” in which a liturgist was critiquing a certain tendency during the seventies for Catholic worship to focus more on the worshipers than on God. For example, he wrote, “Here is a line from a popular hymn at the time: We are the light of the world!” I remembered, and I felt a twinge. “Hey, he’s talking about our song.”

Okay, so Jesus says, “You are the light of the world,” and that works. A few of us pick up guitars and start singing: “We are the light of the world,” and that doesn’t work. Why not? Think about that a minute.

“You are the light of the world.” Who is speaking? Who just said that? It is Jesus who is speaking. Could it be anyone except Jesus who is speaking? Can anyone except Jesus Christ say to another person, “You are the light of the world,” and speak with authority? A man says to the woman he loves, “You are the light of the world”, Is that true? Does the woman conclude from this that she is herself, in very truth, the light of the world? Or does she say to herself, “Yeah, okay, He’s in love, that’s an expression people use when they are in love. He means I am the light of his world, that’s what he means.” and she would be right. That is not what Jesus is saying. Jesus is not saying he’s gone a little gaga over you. Listen to what Jesus is saying. He is saying, “You are light. You are light for the world! You are light for a world that lives in darkness.” Who, except Jesus Christ the Son of God, can say that?

Brothers and sisters, these words are Jesus’ words. When you hear these words, you hear Jesus speak. It is His voice,and when you hear his voice, it means Jesus is present. The living Lord is alive and he is addressing you in the context of an intimate personal encounter. He is speaking in the person of God saying to you with complete authority, “You are the light of the world.”

It’s different when we say, “We are the light of the world.” Who is speaking? Do the people speaking have authority to say this? When we say, “We are the light of the world,” where is Jesus? Maybe an important question we could ask ourselves is: When we say, “We are the light of the world,” do we hear Jesus’ voice?

It cannot be said with authority that we are the light of the world, if we are saying that to ourselves. We are light for the world because Jesus, the Son of God, says we are. “You are light,” are words whose meaning derives from the fact that they are addressed to us by Jesus Christ. But if we are only light because Jesus the Lord says we are, then it is Jesus’ light that is spoken of. It is not our light. This is light that is born from an encounter with a divine person, as when Jesus says to Mother Theresa, “Come be MY light . . .” Mother Theresa said yes, and many people believe she became in all truth Christ’s light for the world. One commentator, near the end of Mother Teresa’s life, reflected that, in the early nineties, she may have been the most powerful and influential woman in the world! If anyone was justified in picking up a guitar and yelping, “I am the light of the world,” it was Mother Theresa. As it turns out, her song was very different. Again and again, over the course of fifty years, Mother Theresa, sang to her spiritual directors her mournful song, returning again and again to the same refrain: “What’s going on?” “Help me to understand, Father.” “There’s just darkness.” “It’s all darkness”. “All I can see is darkness.” “It feels as if I am darkness.” “What is happening to me?”

Mother Theresa was light for the world because she heard Jesus say: “Come, you be MY light.” Jesus was present and living at the center of Mother Theresa’s life saying to her again and again in the most intimate and endearing way, “Come, my bride, my beautiful one, be MY light!” and the bride, lost in wonder at the nearness of God, never thinking to say, “I am light,” but forgetting herself, and addressing her Beloved, saying again and again, “Yes! Yes Lord! I will be YOUR light!”

Fifth Sunday of Ordinary Time

[Scripture Readings: Is 6:1-2a, 3-8; 1 Cor 15:1-11; Lk 5:1-11]

Simon Peter and his fishing partners, had a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad night. Like Alexander, the unlucky little boy in a children’s story, who says, “I went to sleep with chewing gum in my mouth and now there’s gum in my hair. And when I got out of bed I tripped on a skateboard. … I could tell it was going to be a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day.” Sure enough, at breakfast his brothers pull prizes out of their cereal boxes, but he finds nothing. His mother forgets to include dessert in his lunch box, and his best friend won’t play with him anymore. As if that’s not bad enough, after school he goes to the dentist. His brothers have no cavities, but he does. His terrible day ends with — UGH—lima beans for supper, and—YUCK—kissing on television. Feeling totally frustrated Alexander says, “I’m going to move to Australia.“1

Simon Peter and his fishing partners, had a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad night. Like Alexander, the unlucky little boy in a children’s story, who says, “I went to sleep with chewing gum in my mouth and now there’s gum in my hair. And when I got out of bed I tripped on a skateboard. … I could tell it was going to be a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day.” Sure enough, at breakfast his brothers pull prizes out of their cereal boxes, but he finds nothing. His mother forgets to include dessert in his lunch box, and his best friend won’t play with him anymore. As if that’s not bad enough, after school he goes to the dentist. His brothers have no cavities, but he does. His terrible day ends with — UGH—lima beans for supper, and—YUCK—kissing on television. Feeling totally frustrated Alexander says, “I’m going to move to Australia.“1

Simon Peter had a very bad night. He was bone tired from hours of fishing without catching anything. Then Jesus said, “Put out into deep water and lower your nets for a catch.” Simon Peter thought a very bad night was about to become a terrible, horrible, no good day. He didn’t hide his irritation when he said, “Master, we worked hard all night and caught nothing.” There are several Greek words in the New Testament for “Master.” One for the owner of slaves, another for wise teachers; one for religious leaders and another for political rulers. But the word used here is for an overseer at work, a foreman, a task master. On the lips of workers it’s a respectful form of address. But Jesus is not in charge of their fishing. He’s a carpenter not a master fisherman. He’s not even a partner in their work, much less their boss, but that’s what Simon Peter in his frustration calls him, “Boss.”

It might have ended right there if Simon had walked away and gone home to rest. But on the previous Sabbath Jesus cured Simon’s mother-in-law and he was grateful, in debt to Jesus. Simon Peter didn’t share the attitude of someone who said that the height of ambiguous feelings is when you see your mother-in-law driving off a cliff in your new Cadillac. So he decided to do what Jesus asked. But first he said, “At your command I will lower the nets.” “At your command,” at your insistence! He makes it very clear who will be to blame when this no good, very bad idea produces zilch.

It might have ended right there if Simon had walked away and gone home to rest. But on the previous Sabbath Jesus cured Simon’s mother-in-law and he was grateful, in debt to Jesus. Simon Peter didn’t share the attitude of someone who said that the height of ambiguous feelings is when you see your mother-in-law driving off a cliff in your new Cadillac. So he decided to do what Jesus asked. But first he said, “At your command I will lower the nets.” “At your command,” at your insistence! He makes it very clear who will be to blame when this no good, very bad idea produces zilch.

So Simon and his partners lowered their nets. Instead of zilch they caught zillions. Instead of a terrible, horrible, very bad day it became a great day, remembered not so much for what they caught, but as the day on which Jesus caught them. Simon’s mouth opened wide in astonishment but his heart shrank with shame and guilt for his words and actions. Like the prophet Isaiah who saw the Glory of the Lord and let out a cry of woe because he was a man of unclean lips, so also Simon Peter drops to his knees and lets out a cry of woe, “Depart from me Lord, for I am a sinful man.” Now he addresses Jesus not as a boss, a task master, but as Lord, foreshadowing the action of Thomas the Apostle who will fall on his knees in the presence of the risen Christ and proclaim, “My Lord and my God.” Jesus looked at Simon Peter with love and, perhaps, putting a hand on his shoulder said, “Do not be afraid; from now on you will be catching men.” Our sinfulness is wicked. But Jesus washes our hearts clean with his forgiving and loving touch. Simon and his partners were hooked. They left everything and followed him.

Jesus said, “Do not be afraid!” If they had known the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad days that following Christ would cost them, they would have been afraid. Following the call of Christ did not mean their days got easier, often they got harder, as they did for Jesus. The Friday on which he was crucified was the most terrible, horrible, very bad day that ever happened. But Jesus’ love made that Friday Good because it was the day he opened heaven for us. Likewise, even our worst days can become good, transformed by love for Christ. St. Peter toiled and suffered more as a Christian than he ever did as a fisherman, and his life ended upside down on a cross. Yet, his crucifixion was his best day because he loved Christ more than his own life.

Jesus said, “Do not be afraid!” If they had known the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad days that following Christ would cost them, they would have been afraid. Following the call of Christ did not mean their days got easier, often they got harder, as they did for Jesus. The Friday on which he was crucified was the most terrible, horrible, very bad day that ever happened. But Jesus’ love made that Friday Good because it was the day he opened heaven for us. Likewise, even our worst days can become good, transformed by love for Christ. St. Peter toiled and suffered more as a Christian than he ever did as a fisherman, and his life ended upside down on a cross. Yet, his crucifixion was his best day because he loved Christ more than his own life.

The children’s story of little Alexander’s very bad day can’t compare to the true story of another boy’s sufferings, a little Sudanese child named Damare Garang.2 He was seven years old when soldiers attacked his village and sold him into slavery to tend camels. He didn’t know the first thing about it. One day a camel got away. His task master threatened that he would have to pay for it. The next day Damare went to a church service for he was raised as a Christian. When he returned his master asked in an irritated voice, “Where have you been?” Innocently, Damare replied, “To church.” His owner, who was not a Christian, was furious, “Yesterday you lost one of my camels, and today you left them for church!” In a rage he took a board, a hammer and some nails and dragged the young boy to the edge of a field. There he nailed Damare’s feet to the board and drove a nail into each of his knees, then left him to starve to death. Damare lay screaming in agony until a good man happened to pass that way. He was horrified when he saw this tortured child. Like a Good Samaritan, he carried Damare to a hospital where the nails were removed, and then took him under his care. A year and a half later that village was attacked. People were scattered and Damare was separated from his protector. A soldier saw him and realized Damare was from his own tribe. He took him to his commander who adopted the boy as his own because none of Damare’s relatives had survived or could be found.

The children’s story of little Alexander’s very bad day can’t compare to the true story of another boy’s sufferings, a little Sudanese child named Damare Garang.2 He was seven years old when soldiers attacked his village and sold him into slavery to tend camels. He didn’t know the first thing about it. One day a camel got away. His task master threatened that he would have to pay for it. The next day Damare went to a church service for he was raised as a Christian. When he returned his master asked in an irritated voice, “Where have you been?” Innocently, Damare replied, “To church.” His owner, who was not a Christian, was furious, “Yesterday you lost one of my camels, and today you left them for church!” In a rage he took a board, a hammer and some nails and dragged the young boy to the edge of a field. There he nailed Damare’s feet to the board and drove a nail into each of his knees, then left him to starve to death. Damare lay screaming in agony until a good man happened to pass that way. He was horrified when he saw this tortured child. Like a Good Samaritan, he carried Damare to a hospital where the nails were removed, and then took him under his care. A year and a half later that village was attacked. People were scattered and Damare was separated from his protector. A soldier saw him and realized Damare was from his own tribe. He took him to his commander who adopted the boy as his own because none of Damare’s relatives had survived or could be found.

Today Damare is sad that he cannot run like other boys, but said that he has forgiven the slave owner who nailed his feet to a board, because Jesus was nailed to a cross and forgave our sins. He told his story to a missionary who gave him a care package containing mosquito netting, clothes, a new Bible, a soccer ball, and a fishing rod, for Damare loves to fish. With a bright smile he expressed his gratitude to all the people who helped him and then he made a special request, “Please tell Christian children in America to pray for the children of Sudan.” St. Peter and the child, Damare Garang, are witnesses to the power of Christ’s love within us, transforming the worst that can happen into victories of love over evil. When things go very wrong, we don’t have to move to Australia, just move our hearts to love.

Fifth Sunday of Ordinary Time

[Scripture Readings: Is. 6: 1-2a, 3-8; 1Cor. 15: 1-11; Lk. 5: 1-11]

A not uncommon experience is to hear or read a short phrase that stands out as exceptionally meaningful. One that I read a while back and that I reflect on is: Where there is life, there is tension. If there is no tension, you are dead. On first consideration that seems to contradict physical and psychological health. There are a variety of techniques and medications which have reducing stress for their purpose; but I don’t think living in stress is the point of the phrase. As I understand the phrase it points to the fact many of our everyday activities are the result of balancing two opposing movements. Walking is one example of a harmonious balance between relaxing and tensing our muscles. Problems arise when tensions get out of balance. Too much activity and we become fatigued; too much rest and we become lethargic. An extreme introvert can become excessively self-preoccupied and out of touch with his or her surroundings. An extreme extrovert can be lacking in self-awareness and self-knowledge, and end in burnout.

A not uncommon experience is to hear or read a short phrase that stands out as exceptionally meaningful. One that I read a while back and that I reflect on is: Where there is life, there is tension. If there is no tension, you are dead. On first consideration that seems to contradict physical and psychological health. There are a variety of techniques and medications which have reducing stress for their purpose; but I don’t think living in stress is the point of the phrase. As I understand the phrase it points to the fact many of our everyday activities are the result of balancing two opposing movements. Walking is one example of a harmonious balance between relaxing and tensing our muscles. Problems arise when tensions get out of balance. Too much activity and we become fatigued; too much rest and we become lethargic. An extreme introvert can become excessively self-preoccupied and out of touch with his or her surroundings. An extreme extrovert can be lacking in self-awareness and self-knowledge, and end in burnout.

One of the tensions that this morning’s readings bring to my mind is the challenge to balance the awareness of God’s transcendence and the recognition of God’s imminence. God is both beyond us and near to us. We heard in the reading from Isaiah that the world is full of the glory of God. Do we see both God’s glory and the world; or does concentration on one obscure the other? We come out of a not too distant past that put so much emphasis on transcendence that what went on in the world around us seemed relatively unimportant. Now with the advance of secularism, material reminders of religion have faded into the background and a prevalent attitude is what the theologian Karl Rahner called devotion to the world. How are we to balance the tension between the two poles of God’s transcendence and God’s imminence?

Experiencing God’s holiness can be an ambiguous experience. Isaiah was taken out of himself in a vision of God’s holiness; in Jesus, the holy entered into Peter’s everyday work life. The initial reaction of both of them was fear and the recognition of their sinfulness. Perhaps the first question we need to ask ourselves is: Do we want God to enter our lives, or do we prefer an undisturbed and predictable life? God’s presence among us is not a neutral experience. It exposes our true condition and it places demands on us. At the same time God’s presence in our lives also brings healing and empowers us to carry out the work God has for us.

Experiencing God’s holiness can be an ambiguous experience. Isaiah was taken out of himself in a vision of God’s holiness; in Jesus, the holy entered into Peter’s everyday work life. The initial reaction of both of them was fear and the recognition of their sinfulness. Perhaps the first question we need to ask ourselves is: Do we want God to enter our lives, or do we prefer an undisturbed and predictable life? God’s presence among us is not a neutral experience. It exposes our true condition and it places demands on us. At the same time God’s presence in our lives also brings healing and empowers us to carry out the work God has for us.

Isaiah did not simply have a personal and private mystical experience; he was sent on a mission to proclaim God’s word. Similarly Peter and the disciples with him were called to bring the gospel to all creation. Our experiences of God’s presence may not be as dramatic as Isaiah’s and Peter’s. Nevertheless we too are called to work to buildup God’s kingdom in our various situations. This requires that we seek the God who is beyond all that we can think or imagine, and make the encounter with our transcendent God complete in our everyday situations. This is not beyond the ability of any of us. We have God’s word to teach and guide us; we have the sacraments to strengthen us. It is up to us to use the means God has provided for us.