First Sunday of Lent

Scripture Readings: Gen 2:7-9, 3:1-7; Rom 5:12-19; Mt 4:1-11

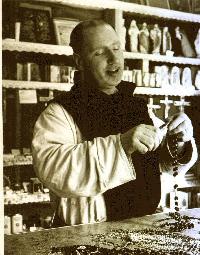

Fr. Pius of New Melleray liked to tell the story of three things we need to know about the devil’s temptations: first, what the devil tempts us to do; second, when the devil tempts us to do it; and third, how the devil he does it.

Fr. Pius of New Melleray liked to tell the story of three things we need to know about the devil’s temptations: first, what the devil tempts us to do; second, when the devil tempts us to do it; and third, how the devil he does it.

The temptations of Jesus are really temptations of Satan. In tempting Christ, Satan is being tempted by his pride. One day, a few years after the conversion of Constantine, Abbot Pachomius called his monks together for a conference. As they gathered around he said to Theodore, a very young monk, “Stand here in the midst of the brethren and speak the Word of God to us.” Some of the seniors were offended. They didn’t think a junior should be teaching them, so they got up to leave. But Pachomius said to them, “Don’t you know how wickedness first began, when the one who shone like the bright morning star fell from heaven through pride? So, put away your superiority for the beginning of wickedness is pride.”1

Isaiah describes Lucifer’s pride: “How you have fallen, O morning star! You said in your heart ‘I will be like the Most High!’ Yet down to the nether world you go, to the depths of hell” (Is. 14:12-14). Instead of becoming like God, Lucifer became Satan, God’s adversary, and lost all his beauty and freedom to be good.

Jesus went into the wilderness to struggle with the Adversary on his own ground. What did Satan tempt Jesus to do? To be proud by showing off his divine power: “If you are the Son of God, command this stone to become bread.” When did Satan tempt Jesus? When he was weak from hunger. But this temptation is not about food. It is about pride, being like Satan. What Jesus would not do to glorify himself he will later do out of compassion, multiplying bread for the hungry, changing water into wine for a newly married couple, and changing bread and wine into his body and blood to share his divine life with us.

Jesus went into the wilderness to struggle with the Adversary on his own ground. What did Satan tempt Jesus to do? To be proud by showing off his divine power: “If you are the Son of God, command this stone to become bread.” When did Satan tempt Jesus? When he was weak from hunger. But this temptation is not about food. It is about pride, being like Satan. What Jesus would not do to glorify himself he will later do out of compassion, multiplying bread for the hungry, changing water into wine for a newly married couple, and changing bread and wine into his body and blood to share his divine life with us.

In the second struggle with Jesus, Satan uses the temptation of a beloved child. “If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down from here, for he will command his angels to support you lest you dash your foot against a stone.” In the beginning Lucifer was a beloved child of God, more beautiful than all the other angels. But he put God’s love to the test. Will an infinitely loving God really let a beloved child suffer eternally for choosing evil? Lucifer tested God and lost his freedom to ever be a good and beautiful child again.

In the second struggle with Jesus, Satan uses the temptation of a beloved child. “If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down from here, for he will command his angels to support you lest you dash your foot against a stone.” In the beginning Lucifer was a beloved child of God, more beautiful than all the other angels. But he put God’s love to the test. Will an infinitely loving God really let a beloved child suffer eternally for choosing evil? Lucifer tested God and lost his freedom to ever be a good and beautiful child again.

In the last struggle with Jesus, Satan is tempted again by his own original sin of pride, “All this will be yours if you prostrate yourself and worship me.” Isaac of Stella describes the ultimate consequences of evil. He writes, “The night will come when you may no longer do good, either to yourself or anyone else. You will lose both the desire and the possibility of doing anything good.”2 That is a description of hell. The temptations of Jesus are really temptations of Satan putting God to the test and worshipping himself over and over again.

Satan is proud, as we often are. Disciples of a holy rabbi said to him, “We are afraid that evil is pursing us.” He replied, “Don’t worry, you are not humble enough for it to pursue you. For the time being, you are still pursuing it.” As a young novice I once went to confession and said I couldn’t think of anything sinful that I had done since my previous confession. Father replied, “Oh, you can’t see the forest because the trees are in the way.” How right he was.

In his old age Fr. Pius became hard of hearing. After confessing my sins to him one day he replied, “I didn’t hear a word you said, but I suppose it’s nothing serious.” When he died some diocesan priests who regularly went to Fr. Pius for confession lamented, “Where are we going to find another deaf confessor?” Isn’t it pride that makes us ashamed to confess our sins and ask forgiveness? Let us use our freedom to choose humility and gratitude as beloved children of God. Isaac of Stella writes, “There is a time for sowing and a time for reaping. Work then, while you can be good, lest the night overtake when you will no longer be able to do anything good.”2

In his old age Fr. Pius became hard of hearing. After confessing my sins to him one day he replied, “I didn’t hear a word you said, but I suppose it’s nothing serious.” When he died some diocesan priests who regularly went to Fr. Pius for confession lamented, “Where are we going to find another deaf confessor?” Isn’t it pride that makes us ashamed to confess our sins and ask forgiveness? Let us use our freedom to choose humility and gratitude as beloved children of God. Isaac of Stella writes, “There is a time for sowing and a time for reaping. Work then, while you can be good, lest the night overtake when you will no longer be able to do anything good.”2

Hell is the place where fallen beloved children who tempted God by their pride and other sins have forever lost the freedom to choose or do anything good. Heaven is the place where all the other beloved children, angels and humans, have by humility and gratitude chosen to love God and now they enjoy the freedom always to choose good and never do anything evil for ever and ever. Now you know what the devil tempts us to do, when he tempts us to do it, and how the devil he does it.

1 Pachomian Koinonia I, The Fist Greek Life of Pachomius, # 77. Translated and edited by Armand Veilleux, Cistercian Studies Series 45.

2. Isaac of Stella, Sermons on the Christian Year, vol. 1, Cistercian Fathers Series, #11, Cistercian Publications, Kalamazoo, MI, 1979, p. 103.

First Sunday of Lent

[Scripture Readings: Deut 26:4-10; Rom 10:8-13; Luke 4:1-13]

Jesus, the Son of God, filled with the Holy Spirit. Here is the blessed Trinity, God for us. As God said to Moses, "I have witnessed your affliction, heard your cry, know well your sufferings. Therefore, I have come down" (Ex 3:7-8). Why of all places in this unspeakably vast and astounding cosmos the eternally living and blissful God would "come down" to the speck of sand that is the Judean desert on this tiny, one-mooned planet of ours to be tried in all ways that we are by the devil, the author of death, is not the least of the things that make the triune God a mystery -- God in solidarity to earth-dwelling sinners, God hungry, hot, liable to the delusions of desire, bearing our pain, enduring our suffering, bearing the guilt of us all, as Isaiah said?

A clue to the mystery is in Paul's words, "there is no distinction between Jew and Greek." God is the bridger of rifts, the mender of rupture, the shepherd restoring the stray, the bond of peace, communion, whose very nature is love imaged best in the two, man and woman, becoming one flesh.

The Trinity that enters our desert of testing appears again on our Cross of shame: "Father, into your hands I commend my spirit." There, the divine mission to reveal the hidden unity of things is accomplished, on his side, in his words, the last, "Father, forgive them," and, "Today you will be with me." The season of Lent heads toward the baptismal liturgy of the Easter Vigil.

For us baptized, Lent is our solidarity with catechumens, our accompaniment of them to their own baptism in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. In baptism we are made children of God. "If you are the Son of God" -- the devil's words to the just-baptized Jesus, Luke is saying, are the tempter's words to us, baptized and risen in Christ, putting off the old man, putting on the new.

Baptized, we are fish out of water, we are in the world, but not of it. If Saint Paul says, "Do not conform yourself to this age," the tempter says, "Conform." And if Paul says, "be transformed by the renewal of your mind," the tempter says, "think like CNN, Fox News, Hilary, or Donald."

Baptism leads us into a war zone, like Jesus in the desert. Baptized to bring good news, the temptation is to return to the familiar and unspectacular, to deny our status as children of God and,

as for Jesus, too, to come down from the Cross of forgiveness and humble service.

Moses told the Israelites in their desert wandering to remember where they had come from. We came from baptism in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Remember your status as children of God. Fix your eyes on the promised land of the unity of God's kingdom. Encourage one another on the Cross of the meanwhile confident that God who demands our very best accepts whatever that is.

First Sunday of Lent

[Scripture Readings: Gen 9:8-15; 1 Pt 3:18-22; Mk 1:12-15]

There is a phrase which I find unusually worded, almost a circulocution or euphemism for what is meant. It is often used when medals of honor are awarded, or at memorials for deceased military or police personnel: “They put themselves in harm's way.” Obviously, it means that they exposed themselves to fatal danger. They were prepared to give their lives for something they thought of greater value than survival. It was better to die for this value or good than to go on living without sacrificing themselves for it. They were living for something worth dying for, something transcendent which gave them meaning. That raises a question for us: are we living for something worth dying for? Are we willing to put ourselves in harm's way?

There is a phrase which I find unusually worded, almost a circulocution or euphemism for what is meant. It is often used when medals of honor are awarded, or at memorials for deceased military or police personnel: “They put themselves in harm's way.” Obviously, it means that they exposed themselves to fatal danger. They were prepared to give their lives for something they thought of greater value than survival. It was better to die for this value or good than to go on living without sacrificing themselves for it. They were living for something worth dying for, something transcendent which gave them meaning. That raises a question for us: are we living for something worth dying for? Are we willing to put ourselves in harm's way?

We might hope that at a “moment of truth” we would respond in a heroic way. But we are really not sure. We might be overwhelmed by fear and self-preservation. We won't know until we are put to the test. Until the moment of truth or crisis. Most of us have some sense that we come alive at those moments when we “die” to our control and planning. A whole-hearted action in which we lose ourselves brings more joy and fulfillment than all those efforts to satisfy our egos. We have the intimations of that experience of Christ: “put to death in the flesh, he was brought to life in the Spirit.” He put himself in harm's way, considered that what he was living for was worth dying for—and we are those he was willing to die for. He suffered that he might lead us to God.

“He remained in the desert for forty days, tempted by Satan.” To be in the desert, in our flesh, is to put oneself in harm's way. The desert is not a comfortable or hospitable place. It reduces one to the barest of needs and dependency. There is no room for the trivial or for pretence. It pushes one to an “inscape” as bare as the landscape. It demands a clarity and simplicity beyond the normal. This is the desert into which we, like Jesus, are pushed by the Spirit. It is a place of testing. A place in which we and God are to discover what is in our hearts. Neither He nor we know what that is until we experience the test, until we put ourselves in harm's way. This is the work of Lent: to know what is in our heart, a cleansing which is an “appeal to God for a clear conscience.” In his Rule, Benedict calls the whole community “during these days of Lent to keep its manner of life most pure.” He is not encouraging greater sexual restraint nor is he speaking to our compulsive needs for rigid order. He is concerned with that clarity, that transparency with which the clean and pure of heart can see God.

“He remained in the desert for forty days, tempted by Satan.” To be in the desert, in our flesh, is to put oneself in harm's way. The desert is not a comfortable or hospitable place. It reduces one to the barest of needs and dependency. There is no room for the trivial or for pretence. It pushes one to an “inscape” as bare as the landscape. It demands a clarity and simplicity beyond the normal. This is the desert into which we, like Jesus, are pushed by the Spirit. It is a place of testing. A place in which we and God are to discover what is in our hearts. Neither He nor we know what that is until we experience the test, until we put ourselves in harm's way. This is the work of Lent: to know what is in our heart, a cleansing which is an “appeal to God for a clear conscience.” In his Rule, Benedict calls the whole community “during these days of Lent to keep its manner of life most pure.” He is not encouraging greater sexual restraint nor is he speaking to our compulsive needs for rigid order. He is concerned with that clarity, that transparency with which the clean and pure of heart can see God. Robert Taft, S.J., says that asceticism is merely a tool to clear away the debris of our lives. “This asceticism is nothing more than the necessary objectivity and distance from whatever is impermanent and secondary in the human endeavor; the self-discipline necessary to maintain true freedom and makes the right choices; the destruction of egoism by the honest person who has the courage to stand naked before self and God. The point is an openness to new life, and through it, openness to others.” This honesty and freedom are tempered, tested, and become real through our willingness to live in simplicity and openness before God and others. These bring a new aliveness and sensitivity to the leading of the Spirit, affirming those covenant bonds which unite us to one another and the whole of creation.

Robert Taft, S.J., says that asceticism is merely a tool to clear away the debris of our lives. “This asceticism is nothing more than the necessary objectivity and distance from whatever is impermanent and secondary in the human endeavor; the self-discipline necessary to maintain true freedom and makes the right choices; the destruction of egoism by the honest person who has the courage to stand naked before self and God. The point is an openness to new life, and through it, openness to others.” This honesty and freedom are tempered, tested, and become real through our willingness to live in simplicity and openness before God and others. These bring a new aliveness and sensitivity to the leading of the Spirit, affirming those covenant bonds which unite us to one another and the whole of creation.

We are still afflicted by what St. Benedict calls “neglect” and what Pope Francis has emphasized in his Lenten Address of 2015 as “indifference.” Francis says that this indifference has reached global proportions and causes us to withdraw and shut the door to the movement of God breaking in to our lives. Comfort and ease make us forget God and the needs of others. We find it easier to live at a distance, to buffer our own lives with security, defensiveness and distraction. We are unwilling to expose ourselves. Rather than finding the needs of others as an appeal to our consciences, they become sources of fear and potential terror. We are fascinated and addicted to convenience. We are intolerant of pain or delay. We are unwilling to endure a pause between a felt need and its satisfaction, impatient and ready to manipulate and exploit whatever resources of the world and creation are available. We are afflicted with what Julia Kristeva calls “accelerated hyperconnection.” At its root, we are intolerant of our own selves—selves which we sense to be an incurable sore, an eternal anxiety that dominates our lives while it refusing to identify itself. Putting ourselves in harm's way, discovering what it is that we would be willing to die for, is to unmask what it is that is in our hearts. It is to find in Lent a patient immersion into the landscape of the desert and the inscape our our souls.

We are unwilling to expose ourselves. Rather than finding the needs of others as an appeal to our consciences, they become sources of fear and potential terror. We are fascinated and addicted to convenience. We are intolerant of pain or delay. We are unwilling to endure a pause between a felt need and its satisfaction, impatient and ready to manipulate and exploit whatever resources of the world and creation are available. We are afflicted with what Julia Kristeva calls “accelerated hyperconnection.” At its root, we are intolerant of our own selves—selves which we sense to be an incurable sore, an eternal anxiety that dominates our lives while it refusing to identify itself. Putting ourselves in harm's way, discovering what it is that we would be willing to die for, is to unmask what it is that is in our hearts. It is to find in Lent a patient immersion into the landscape of the desert and the inscape our our souls.

In a beautiful image, Pope Francis speaks of the Church, the sacraments, this time of Lent and repentance as “holding the door open for God.” We do not heal ourselves. We do not save ourselves. We do not cleanse ourselves, and then present ourselves to God.  It is by opening our eyes to admit the ongoing complicity of our lives with sin and evil that we hold open the door of our hearts to Christ. We find in there both the angels and the wild beasts. We find our capacity for great good and for great evil. It is this capacity that Christ comes to cleanse and to heal. As Pope Francis says: “Only those who have first allowed Jesus to wash their own feet can then offer this service to others …. We can only bear witness to what we ourselves have experienced. Christians are those who let God clothe them with goodness and mercy, with Christ, so as to become like Christ servant of God and others.” Knowing and experiencing that Christ puts himself in harm's way for us becomes the opening to a life of belief. An opening to a life impelled by the Spirit for engaging fully in the human adventure through which we are led to God.

It is by opening our eyes to admit the ongoing complicity of our lives with sin and evil that we hold open the door of our hearts to Christ. We find in there both the angels and the wild beasts. We find our capacity for great good and for great evil. It is this capacity that Christ comes to cleanse and to heal. As Pope Francis says: “Only those who have first allowed Jesus to wash their own feet can then offer this service to others …. We can only bear witness to what we ourselves have experienced. Christians are those who let God clothe them with goodness and mercy, with Christ, so as to become like Christ servant of God and others.” Knowing and experiencing that Christ puts himself in harm's way for us becomes the opening to a life of belief. An opening to a life impelled by the Spirit for engaging fully in the human adventure through which we are led to God.

First Sunday of Lent

[Scripture Readings: Deut 26:4-10; Rom 10:8-13; Lk 4:1-13 ]

We begin Lent today with a very important story about what it is like to be a Christian …on the inside. Luke tells us that Jesus was filled with the Holy Spirit, the Spirit that descended upon Him at baptism. This and the voice from heaven identifying Him as “…my son, my beloved…”, “began His work.” And the first thing this Spirit did was to lead Him into the dessert. The profound call of Jesus (and of any of us) leads to the profound question: “What does it mean? How does one live out this call?” In other words, what should I believe; how should I behave? The desert answers those questions by educating Him about what He should care about. “Educate” (e-ducere) means “to draw out.” The desert will draw out, from the inside, what is truly in His heart, what He truly cares about; what matters most. Desert experiences will do that to any of us.

We begin Lent today with a very important story about what it is like to be a Christian …on the inside. Luke tells us that Jesus was filled with the Holy Spirit, the Spirit that descended upon Him at baptism. This and the voice from heaven identifying Him as “…my son, my beloved…”, “began His work.” And the first thing this Spirit did was to lead Him into the dessert. The profound call of Jesus (and of any of us) leads to the profound question: “What does it mean? How does one live out this call?” In other words, what should I believe; how should I behave? The desert answers those questions by educating Him about what He should care about. “Educate” (e-ducere) means “to draw out.” The desert will draw out, from the inside, what is truly in His heart, what He truly cares about; what matters most. Desert experiences will do that to any of us.

The desert (whether a location or an experience of life) is desolate. Life-giving water is rare. It is a place where things are not like they used to be. Yet, it is also a privileged place. It is on the way to the Promised Land of milk and honey.

Jesus re-lives the desert experience of the exodus of His people centuries earlier. Then they had believed they were abandoned to hunger; they had behaved in rebellion; and they cared only for the pleasure and security of the familiar.

With Jesus the desert incident becomes an exodus of the heart from slavery in Egypt. We must remember it is the Lord Himself who leads us and gifts us. Taking for granted the gifts and forgetting the Giver is not what it is like to be a Christian on the inside.

With Jesus the desert incident becomes an exodus of the heart from slavery in Egypt. We must remember it is the Lord Himself who leads us and gifts us. Taking for granted the gifts and forgetting the Giver is not what it is like to be a Christian on the inside.

The fundamental interior issue of temptation is the desire to be other than human. Thus the danger in temptation is that it weakens our desire to delight in God. If Jesus is going to “speak as one with authority” He must go through these temptations and maintain allegiance to the covenant.

If He is to proclaim liberty to captives; recovery of sight to the blind; and release to prisoners He must experience the occasions for these spiritual conditions. He must have struggled with what to believe, how to behave, and what to care about. He must meet each task with a heart that delights only in the Father.

Jesus' responses to the temptations all come from the book of Deut., the book in the bible most concerned with obedience. It is there that we find the purpose of temptation: “Remember the long way that the LORD your God has led you these forty years in the desert, in order to humble you, testing you to know what was in your heart, whether or not you would keep his commandments” (DT 8:2)

In Luke's gospel, Jesus first decides what he cares most about. After a long fast He wants what will nourish Him. Temptation is aimed precisely at changing what we want. To get the immediate gratification of His intense hunger, Jesus is not asked to hate God or outright reject Him. All He needs to do is forget God for a while and focus on “more important things.”

In Luke's gospel, Jesus first decides what he cares most about. After a long fast He wants what will nourish Him. Temptation is aimed precisely at changing what we want. To get the immediate gratification of His intense hunger, Jesus is not asked to hate God or outright reject Him. All He needs to do is forget God for a while and focus on “more important things.”

This is the critical temptation. Here Jesus, and we, must choose between a preference for self-satisfaction or for authentic value, for the important-in-itself. Had He chose self-satisfaction, the other two temptations would not be necessary. The subject of all the temptations is the primacy of God.

Two important things are shown us today about what it is like to be a Christian on the inside: First, We must take on a fundamental moral attitude that will carry us through all subsequent temptations away from God and His order. That fundamental moral attitude is reverence.

Reverence is a contemplative, listening attitude that appreciates and lets be the other. Jesus lets a stone be a stone and bread be bread. Reverence stands back in admiration. It seeks to serve what it revere's and admires so that the thing can become what it is meant to be in the Divine Order.

Second: We do not confront temptations like mud puddles we stepped in. Rather, these situations and how we understand them are a function of the kind of people we are. As lovers of God we confront some difficulties precisely because we are lovers of God. We must make up our minds that unbroken fidelity is important.

Second: We do not confront temptations like mud puddles we stepped in. Rather, these situations and how we understand them are a function of the kind of people we are. As lovers of God we confront some difficulties precisely because we are lovers of God. We must make up our minds that unbroken fidelity is important.

To this end, Reverence is the first step in St. Benedict's way of humility, a way ordered to conversion of life. The first step of humility begins the formation of a monastic conscience.

It is with this fundamental attitude that a monk must face the temptations that will test the kind of man he has become.

Reverence and faithful adoration are what it is like to be a Christian …on the inside.

First Sunday of Lent

[Scripture Readings: Deut 26:4-10; Rom 10:8-13; Lk 4:1-13 ]

At the Baptism of the Lord, we learn that He is filled with the Holy Spirit. It is the Spirit Who leads Jesus into the desert where He is without food for forty days, with wild beasts, tempted by the devil, and ministered to by angels. At baptism, we are filled with the same Spirit, Who leads us in following Christ. How do we recognize this guidance by the Holy Spirit? The Church is our guide.

At the Baptism of the Lord, we learn that He is filled with the Holy Spirit. It is the Spirit Who leads Jesus into the desert where He is without food for forty days, with wild beasts, tempted by the devil, and ministered to by angels. At baptism, we are filled with the same Spirit, Who leads us in following Christ. How do we recognize this guidance by the Holy Spirit? The Church is our guide.

Each Friday of the year, and the season of Lent, are intense moments of the Church’s penitential practice. As far as food goes, the requirements are not demanding even for adults. Pastors and parents are to see to it that children, who are not required to abstain or fast, still are brought up in an authentic sense of penance.

In our family, as in many, the kids gave up candy. This was not very demanding since we just finished off the house’s supply on fat Tuesday, then didn’t even see any during Lent. Of course, when Easter came, mom and dad told us that the baskets were filled by a roving rabbit. These contained far more candy than we would normally have seen during eight weeks, and it did not last us even one week.

My father had a regular Lenten custom. He claimed to give up okra and pickled pig’s feet. As we grew and realized that he never ate either of these, we caught the hint: while our observance of Lent was indeed our parents’ concern, we need not be concerned about what others did for Lent.

From our Catholic school and then in parish religious education, we learned to give alms with the Rice Bowl program. We took part in the stations of the cross in school and at the parish. These simple practices are very common for children, and do provide a basic beginning to authentic penance: prayer, fasting, and alms giving. But what is behind the practice? Why do we do it? Do we fast just to lose weight or stay slim; is fasting just Christian dieting? In the Church each year, Lenten penance solemnly observed, unites the Church to Jesus in the desert. The self mastery involved in giving up even good things strengthens us to avoid all forms of sin.

From our Catholic school and then in parish religious education, we learned to give alms with the Rice Bowl program. We took part in the stations of the cross in school and at the parish. These simple practices are very common for children, and do provide a basic beginning to authentic penance: prayer, fasting, and alms giving. But what is behind the practice? Why do we do it? Do we fast just to lose weight or stay slim; is fasting just Christian dieting? In the Church each year, Lenten penance solemnly observed, unites the Church to Jesus in the desert. The self mastery involved in giving up even good things strengthens us to avoid all forms of sin.

One former marine told me about his most difficult Lenten fast: cigarettes and booze. After Easter, he was most pleased with himself. His supervisor took him out to lunch, handed him a pack of cigarettes and ordered him a martini. No, no, I’ve given them up for good. His boss replied: we’ve put up with your giving up too long: you’ve made our lives miserable. Drink, smoke, now. That proved the most difficult part of his Lent, learning of the penance he had inflicted on his co-workers.

In the desert, Jesus did not have to atone for any sin of His own, but He did have to fight temptation. Following Him into the desert, we will face the beasts of hunger and the need to practice self control. Practicing ever more intensely a self-mastery, we will struggle to silence the distractions of the world and our own bodies, quieting our hearts to listen for God in the place God most often speaks, the heart. God is not the only one speaking even there: the world, the flesh, and the devil all distract the heart from God.

Will we face a dramatic series of temptations as did Jesus? Maybe, but unlikely. If we used this to mark a successful Lent, we would be putting God to the test! On this point, our Lord’s instructions are clear: pray that you will not be put to the test.

Will we face a dramatic series of temptations as did Jesus? Maybe, but unlikely. If we used this to mark a successful Lent, we would be putting God to the test! On this point, our Lord’s instructions are clear: pray that you will not be put to the test.

Jesus faced temptations to satisfy his own hunger, to accept earthly power, and to tempt God. He remained a faithful, humble, and obedient son, reversing Adams’ sin which had been repeated by the Israelites in the desert. Leaving the desert, Jesus began his public ministry which concluded with the Paschal mystery: the Last Supper, His Crucifixion, death, and Resurrection. Jesus did everything out of obedience to the Father and out of love for us.

We can follow Him, accepting Lenten penance as part of our calling within the Church; something individuals do alone, quietly, without drawing attention to ourselves, yet, something that benefits the whole body of Christ. This is one way we live out the baptismal priesthood. It is fitting to offer our Lent as a way of discerning God’s particular call in our lives: is He calling me to a different vocation? Is He calling me to continue my current vocation with greater zeal?

We are still in a year dedicated by the Church to the ordained priesthood. The church encourages us to use this year to meditate upon the meaning of this special calling, and to pray for ordained priests even if God calls us to another vocation.

Let us seek a clear articulation of the distinction between the priesthood of the baptized as members of the Body of Christ, and the ordained priesthood which is configured in a unique way to Christ to serve the Church by acting in the person of Christ the head. The ordained priesthood involves great sacrifice; if we cannot explain to men the difference between baptismal and ordained priesthood then we cannot expect them to accept this sacrificial service. A church without the ordain priesthood would be a community without the Eucharist, it could be at best a shadow of the Church that Jesus Christ died to establish.

Let us seek a clear articulation of the distinction between the priesthood of the baptized as members of the Body of Christ, and the ordained priesthood which is configured in a unique way to Christ to serve the Church by acting in the person of Christ the head. The ordained priesthood involves great sacrifice; if we cannot explain to men the difference between baptismal and ordained priesthood then we cannot expect them to accept this sacrificial service. A church without the ordain priesthood would be a community without the Eucharist, it could be at best a shadow of the Church that Jesus Christ died to establish.

Let us pray for the particular men who are considering vocations to the priesthood. For the young, many find it hard to be free to attend the seminary and still have the security of a job should they realize that God is not calling them to the priesthood. Such security is an aid to freedom, and the ordained priesthood and only be accepted in freedom. Older men find a different struggle; if they are established in business, how much time can they afford to set aside to seek God’s will? These difficulties arise for men and women considering religious life as well, but this year, the Church asks us to pray for priests.

Fidelity to the Church, even in disciplinary practices like the observation of Lent, is extremely important in fostering vocations. The discipline of the priesthood, like that of religious life, is largely discipline, not dogma. As part of the mystery of life in the Church, our Lord tells us that those who are faithful in small things will be entrusted with the care of great things. The Church gives us many reasons to be faithful to our discipline of Lent.

First Sunday of Lent

[Scripture Readings: Gen 9:8-15; 1 Pt 3:18-22; Mk 1:12-15]

A novice approached his novice master on the novice’s first day in novitiate and asked “How did you become holy?” The novice master replied, “Two words: Right choices.” The novice asked “How does one learn to choose rightly?” The master replied “One word.” “What is that?” “Growth.” The novice continued, “What occasions this growth?” The novice master answered “Two words.” “And what are those?” the novice asked. The novice master replied “Wrong choices!”

A novice approached his novice master on the novice’s first day in novitiate and asked “How did you become holy?” The novice master replied, “Two words: Right choices.” The novice asked “How does one learn to choose rightly?” The master replied “One word.” “What is that?” “Growth.” The novice continued, “What occasions this growth?” The novice master answered “Two words.” “And what are those?” the novice asked. The novice master replied “Wrong choices!”

That story is very appropriate for beginning the observance of Lent, a time of conversion. It tells us making mistakes won’t cause us difficulties; defending our mistakes will cause us difficulties!

Immediately prior to today’s gospel story Jesus had a deeply moving experience that set the tone for his time in the desert and his ministry “with authority.” He had just been baptized by John and heard the Father say “You are my beloved son; with you I am well pleased.” It was with this experience on his mind that the Spirit drove him into the desert to be alone. Like the heavens, his soul must have opened and he was affected in his innermost identity, his innermost understanding of who he was.

Sonship and temptation seem to be two sides of the same coin. St. John Vianney tells us Satan does not and need not tempt those who do not live with God-consciousness. This deep, inner experience is precisely what Satan aims at. The inner experience of God is called conscience. Conscience is another word for “heart.” Jesus clearly had a good, correct conscience, a wholehearted love for the Father, but Satan thought it remained to be seen if he could prudently act on it.

Sonship and temptation seem to be two sides of the same coin. St. John Vianney tells us Satan does not and need not tempt those who do not live with God-consciousness. This deep, inner experience is precisely what Satan aims at. The inner experience of God is called conscience. Conscience is another word for “heart.” Jesus clearly had a good, correct conscience, a wholehearted love for the Father, but Satan thought it remained to be seen if he could prudently act on it.

We, too, have a God-given identity, a vocation. We, too, have a deep, inner experience we are impelled to live out. Lent is a time for us, brothers, to think back to our own “You are my beloved son” experience. It was the experience that brought us to the monastery. We, too, hear the clear and correct voice of conscience. However, a clear idea of the true and ultimate good, of what matters most was not enough. We could not just “get the idea.” A well-formed conscience is not a guarantee that we will be able to choose and act in accord with it.

Matthew and Luke describe the depths of the heart that temptation tries to shake. Mark tells us only that “Satan tempted Jesus.” The word “Satan” means The Accuser. The purpose of temptation is accusation. If we violate that deep, inner experience of being a “beloved son,” he accuses us of insincerity. Insincerity means that we don’t truly want to live God’s way of life. In a particular situation, I don’t think God’s goods are my goods. By accusing our sincerity, Satan arouses our pride. Pride is an effort at avoiding a broken heart. The broken heart — what we call poverty of spirit—comes from undertaking a great love and realizing how far short of it we fall. In truth the issue we are faced with in temptation is not sincerity; it is freedom. To live faithful to conscience, to our relationship of son, we must be free. We must be free from self-gratification and for self-gift. Jesus and St. Benedict show us that this freedom to live at peace with conscience is given in humility.

Dom Andre Louf, in his little book The Way of Humility, wonderfully describes not the virtue of humility but the “state” of humility as being the Christian response to temptation. Both the Christian in the world and the monk in the desert face temptation of this deep inner experience of God throughout their lives. The difference, he notes, is that the monk, led by the Spirit, chooses to walk toward the temptation. That is why we begin each hour of the Office with “O God, come to my assistance.”

In the state of humility, temptation leaves us flat on the ground in powerlessness. Temptation rightly discourages our confidence in our will power; we know what to do, but lack the power. That is why later Mark tells us that Jesus’ advice for temptation is “Watch and pray.” It is in temptation that we find our true relationship with the Father, that we find what it really means to be a “beloved son.” It means we find ourselves totally dependent on Him, on his care and protection. Sometimes we learn that by failing. It means that we realize we are complete and sufficient beings precisely in that dependence. That is what we are when we are “only human.” That is humility. That is the art of being human.

The Spirit drove Jesus into the desert so that he could experience the Father’s care and protection in the worst that could happen: the rupture of the relationship.

Like Christ, we must trust the Father more than self in times of that same temptation.

In the end, we are with the wild beasts and the angels. Facing our failures and renouncing the beasts of prideful self-reliance, though, will mean a broken heart. When we prefer nothing whatever to Christ, we are free to prefer a broken heart to righteousness apart from God.

Then the angels will minister to us. Each of us can think back to seniors that we knew when we were novices. By their example, they taught us how to be monks; they were free to be a self-gift. They taught us how to walk toward temptation. The most important lesson they taught us was how to live peacefully with a broken heart.

First Sunday of Lent

[Scripture Readings: Gen 2:7-9, 3:1-7; Rom 5:12-19; Mt 4:1-11]

Keep giving Satan an inch and he will become a ruler! In a book of thirty-one letters from hell, C.S. Lewis exposes the wily ways of the devil as the demon Screwtape teaches his nephew Wormwood the art of temptation. Martin Luther writes, “The best way to drive out the devil, if he does not yield to texts of Scripture, is to jeer and flout him, for he cannot bear scorn.“1 That is what C.S. Lewis does best, mocking devils with names like “our father below,” Glubose, Scabtree, Triptweeeze, Slubgob, and Toadpipe. At the annual dinner of the Tempters’ Training College for young devils, Screwtape, who is the guest of honor, gives a toast saying, “Your Imminence, your Disgraces, my Thorns, Shadies, and Gentledevils: a toast to Principal Slubgob and the College [of Tempters]!” 2

Keep giving Satan an inch and he will become a ruler! In a book of thirty-one letters from hell, C.S. Lewis exposes the wily ways of the devil as the demon Screwtape teaches his nephew Wormwood the art of temptation. Martin Luther writes, “The best way to drive out the devil, if he does not yield to texts of Scripture, is to jeer and flout him, for he cannot bear scorn.“1 That is what C.S. Lewis does best, mocking devils with names like “our father below,” Glubose, Scabtree, Triptweeeze, Slubgob, and Toadpipe. At the annual dinner of the Tempters’ Training College for young devils, Screwtape, who is the guest of honor, gives a toast saying, “Your Imminence, your Disgraces, my Thorns, Shadies, and Gentledevils: a toast to Principal Slubgob and the College [of Tempters]!” 2

The bible does not treat Satan so lightly. St. Peter writes, “Your adversary the devil is prowling around like a roaring lion seeking someone to devour” . In a contemporary work of fiction, devilish cohorts of the ultimate adversary of all that is good are called dementors. J.K. Rowling writes, “Dementors are among the foulest creatures that walk this earth. They infest the darkest, filthiest places, they glory in decay and despair, they drain peace, hope, and happiness out of the air around them. … Get too near a dementor and every good feeling, every happy memory will be sucked out of you. If it can, the dementor will feed on you long enough to reduce you to something like itself … You’ll be left with nothing but the worst experiences ….”3 “When [someone] goes over to the Dark Side, there’s nothing and no one that matters to them anymore. … [T]he terrible power of dementors forces their victims to relive the worst memories of their lives, and drown, powerless, in their own despair.” 4

If we saw our demonic tormentors for what they really are we would be scared silly and resist them mightily. But C.S. Lewis writes, “they know the surest way to lead us to hell is the gradual one—the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without signposts.“5 The Manchester Art Gallery in England has a painting by John Spencer Stanhope on the temptation of Eve. The serpent is whispering into her ear, and you can tell by the look on her face that she is enticed by the temptation. Eve does not notice the serpent’s long tail going up and over a branch, bending it down to her raised hand, so that her fingers wrap easily around the forbidden fruit. Knowing the consequences we want to cry out, “Don’t touch it!” But it’s too late, she had already sinned before she touched it.

If we saw our demonic tormentors for what they really are we would be scared silly and resist them mightily. But C.S. Lewis writes, “they know the surest way to lead us to hell is the gradual one—the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without signposts.“5 The Manchester Art Gallery in England has a painting by John Spencer Stanhope on the temptation of Eve. The serpent is whispering into her ear, and you can tell by the look on her face that she is enticed by the temptation. Eve does not notice the serpent’s long tail going up and over a branch, bending it down to her raised hand, so that her fingers wrap easily around the forbidden fruit. Knowing the consequences we want to cry out, “Don’t touch it!” But it’s too late, she had already sinned before she touched it.

Baldwin of Ford, an early Cistercian author, writes that the first sin was disbelief. The serpent asked the woman if God really said they were not to eat from any of the trees of the garden. She replied, “We may eat the fruit of the trees in the garden, but of the tree in the middle of the garden God said, ‘You must not eat it, nor touch it, under pain of death.’ ” Then the serpent said to the woman, “No, you will not die. God knows the day you eat it, your eyes will be open and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” Adam and Eve believed the serpent rather than God. By a proud judgment they convicted God of being a liar. Before they ate the fruit they had already fallen into disgrace. They transferred to the glory of Satan the honor of faith which should have been shown to God’s words.6 They made Satan a god, and God a Deceiver. The serpent said they would not die. But Satan lied. After their willful disbelief and their subsequent disobedience they did die, first spiritually—when the Holy Spirit was driven out of their disbelieving hearts and Satan entered them; and later physically—when they returned to dust.

To restore the life that Adam and Eve had lost, Jesus, after his baptismal commitment to die on the cross for us, was led by the Holy Spirit to the place of temptation. It is no longer a garden but a wasteland, because demons deliver decay and despair after they deceive . In Sister Clairvaux’s icon of the Nativity in our guest house meditation hallway, St. Joseph is sitting on the ground and a devil stands before him like a vulture tempting Joseph to believe the worst. The leaves on plants near the Seducer wither away in the evil presence. But Satan found no room in the hearts of Mary and Joseph. Instead, the Tempter witnessed with great fear the birth of a Child that would drive him off his throne in the hearts of people he claimed as his kingdom.

To restore the life that Adam and Eve had lost, Jesus, after his baptismal commitment to die on the cross for us, was led by the Holy Spirit to the place of temptation. It is no longer a garden but a wasteland, because demons deliver decay and despair after they deceive . In Sister Clairvaux’s icon of the Nativity in our guest house meditation hallway, St. Joseph is sitting on the ground and a devil stands before him like a vulture tempting Joseph to believe the worst. The leaves on plants near the Seducer wither away in the evil presence. But Satan found no room in the hearts of Mary and Joseph. Instead, the Tempter witnessed with great fear the birth of a Child that would drive him off his throne in the hearts of people he claimed as his kingdom.

Now, thirty years later, these two great Adversaries come face to face in the desert. The Liar and the Truth. The creature and the Creator. The beast and the Good Shepherd who seeks the lost. If Slubgob, if this foulest of devils, if this demonic tormentor can turn the heart of Jesus, then all will be lost, even Jesus, and God’s goodness will die. The first temptation is gently provocative. “If you are the Son of God turn these stones into loaves of bread.” Prove it! Don’t ask us for belief. Later, children of the father of lies will repeat this temptation, “If you are the Son of God, come down from the cross!” . But disbelief is the way to death. Jesus replies, “One does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God” . As all was lost by disbelief in God’s word at the Fall, so God wills that the way back to life is to repent and believe in his words. But Satan won’t!

The second temptation again rejects the way of faith and stubbornly repeats the temptation for a sign: “If you are the Son of God throw yourself down, for it is written, ‘He will give his angels charge of you … lest you strike your foot against a stone.’” Satan’s stubbornness, the hardness of his heart is his hell. Every mortal sin can be forgiven except stubbornness in evil. The refusal to repent and believe puts God’s infinite goodness to the test, tempting God to forgive where there is no repentance, no belief in his words. Jesus replies, “You shall not tempt the Lord your God” . But Satan will! Again and again.

The third temptation exposes the real motivation behind everything that Satan does. The Seducer repeats his own original sin of pride, wanting God’s place, wanting to be worshipped. The Deceiver says, “All these [kingdoms] I will give you, if you will fall down and worship me.” Jesus replies, “It is written, ‘You shall worship the Lord your God and him only shall you serve’” . Who is being tested here? Is it Jesus? Or, is Jesus testing Satan, tempting him to faith and worship? And who fails the test to be good? It is clear. Jesus said, “Begone, Satan! And the devil left him.” Satan and his cohorts are being driven out, cast down from their thrones in the hearts of those who believe, worship, and obey.

Archbishop Sheen writes that “We have more temptations to be good than we have to be bad.“7 We have the voice of conscience, the good example of others, the guidance of God’s word in the Sacred Scriptures, the consolations of God’s presence in the Liturgy, the lives of the saints, the encouragement of parents, friends, teachers and preachers, and the good inspirations of angels and the Holy Spirit. Keep believing and giving Jesus the present moment; he will become our eternal happiness.

First Sunday of Lent

[Scripture Readings: Gen 9:8-15; 1Pt 3:18-22; Mk 1:12-15]

As a guest at a Benedictine monastery many years ago, I was at a festive meal seated at a table with six other monks enjoying the lively conversation Benedictines are good at. Two monks that day, were celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of their Solemn Profession, and one of the jubilarians was sitting at my table — I’ll call him Samuel. Samuel was not an endearing person; he was a very, very difficult monk, and over the course of twenty-five years in the monastery, he had hurt or offended his brothers too many times to count. Nobody could work with him. He’d be given a job assignment, and within three weeks, his brothers would be begging the abbot to transfer him somewhere—anywhere else. Celebrating the anniversary of a monk whom many of the brothers, found it difficult even to have a conversation with was a delicate procedure, but they were managing pretty well, until Fr. Marion, a very sweet, simple old monk, came up behind Samuel, gave him a great big affectionate hug, and said: “Congratulations brother!” “Twenty-five years perseverance in the Lord’s service—we’re so proud of you!” Now, nothing irritated Samuel more than kind words, from a sweet old monk and he replied at once very sarcastically: “That’s right father, I’ve been a monk for twenty-five years, and its been twenty-five years of pure hell.” Fr. Jeremy, sitting across from Samuel, smiled and said cheerfully: “Yes brother—yes, of course . . . and what was it like for you?” Every body at the table burst out laughing, and then—Samuel began to laugh; he laughed and laughed, like he couldn’t stop, until finally tears came to his eyes. He laughed—until he wept.

As a guest at a Benedictine monastery many years ago, I was at a festive meal seated at a table with six other monks enjoying the lively conversation Benedictines are good at. Two monks that day, were celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of their Solemn Profession, and one of the jubilarians was sitting at my table — I’ll call him Samuel. Samuel was not an endearing person; he was a very, very difficult monk, and over the course of twenty-five years in the monastery, he had hurt or offended his brothers too many times to count. Nobody could work with him. He’d be given a job assignment, and within three weeks, his brothers would be begging the abbot to transfer him somewhere—anywhere else. Celebrating the anniversary of a monk whom many of the brothers, found it difficult even to have a conversation with was a delicate procedure, but they were managing pretty well, until Fr. Marion, a very sweet, simple old monk, came up behind Samuel, gave him a great big affectionate hug, and said: “Congratulations brother!” “Twenty-five years perseverance in the Lord’s service—we’re so proud of you!” Now, nothing irritated Samuel more than kind words, from a sweet old monk and he replied at once very sarcastically: “That’s right father, I’ve been a monk for twenty-five years, and its been twenty-five years of pure hell.” Fr. Jeremy, sitting across from Samuel, smiled and said cheerfully: “Yes brother—yes, of course . . . and what was it like for you?” Every body at the table burst out laughing, and then—Samuel began to laugh; he laughed and laughed, like he couldn’t stop, until finally tears came to his eyes. He laughed—until he wept.

Fr. Jeremy’s witty response spoke to a truth the monks at the table were trying hard not to think about: Samuel, for twenty-five years, had been a burden to his brothers—even a kind of affliction.  What we realized the moment after Jeremy spoke was that, the truth was deeper than that: here were those very same brothers twenty-five years later, all gathered around Samuel, breaking bread with him, at the table of fellowship, enjoying a good laugh with him. Samuel was loved. Celebrating his anniversary made sense after all: we were celebrating God’s mercy made visible by his brother’s willingness to forgive Samuel the years of pain he had caused them. Sitting at that table, twenty-five years seemed to collapse in a moment and their meaning made clear: it was all about mercy, a fantastic, mysterious largeness of love glimpsed in Fr. Jeremy’s teasing remark. It was as if, for the six of us sitting there, time had come to a fullness; life had been made complete. For an instant, we glimpsed eternity and we realized Samuel—was going to be okay; and we were going to be okay. Everything was going to be okay—and this insight made us laugh. And Samuel, the notoriously nasty monk, laughed harder and longer than anyone; laughed until he cried.

What we realized the moment after Jeremy spoke was that, the truth was deeper than that: here were those very same brothers twenty-five years later, all gathered around Samuel, breaking bread with him, at the table of fellowship, enjoying a good laugh with him. Samuel was loved. Celebrating his anniversary made sense after all: we were celebrating God’s mercy made visible by his brother’s willingness to forgive Samuel the years of pain he had caused them. Sitting at that table, twenty-five years seemed to collapse in a moment and their meaning made clear: it was all about mercy, a fantastic, mysterious largeness of love glimpsed in Fr. Jeremy’s teasing remark. It was as if, for the six of us sitting there, time had come to a fullness; life had been made complete. For an instant, we glimpsed eternity and we realized Samuel—was going to be okay; and we were going to be okay. Everything was going to be okay—and this insight made us laugh. And Samuel, the notoriously nasty monk, laughed harder and longer than anyone; laughed until he cried.

Every year when we hear Jesus proclaim in the scriptures: “This is the time of fulfillment. Repent and believe in the gospel!” we say to ourselves: “Oh no . . . is it Lent already?”, but it’s okay to think that, because the one we hear calling loves us and is endlessly tolerant of our human weakness and grumbling. Would you like to say to Jesus?  “The Lenten discipline last year was pure hell . . .” You can talk that way to Jesus, he is patient with us. In the midst of our grumbling we might meditate on Jesus’ patience. Better yet, when you catch yourself complaining about Lent last year, take a moment and reflect what it might have been like for him. Sitting with those six other monks at table that day, I experienced time coming to a fulfillment. Jesus is saying that now; this moment at the beginning of Lent, is THE time of fulfillment. In Jesus’ words, all history is collapsing in a moment, and this moment is revealing to us the meaning of all events that have occurred in the world since the beginning of time: the deepest meaning of it all is mercy. It’s all about mercy.

“The Lenten discipline last year was pure hell . . .” You can talk that way to Jesus, he is patient with us. In the midst of our grumbling we might meditate on Jesus’ patience. Better yet, when you catch yourself complaining about Lent last year, take a moment and reflect what it might have been like for him. Sitting with those six other monks at table that day, I experienced time coming to a fulfillment. Jesus is saying that now; this moment at the beginning of Lent, is THE time of fulfillment. In Jesus’ words, all history is collapsing in a moment, and this moment is revealing to us the meaning of all events that have occurred in the world since the beginning of time: the deepest meaning of it all is mercy. It’s all about mercy.

The Lenten Season has begun and we are called by the Lord to repent of our sins. Don’t think this needs to be something terribly difficult. Could it be more difficult for us than for Samuel? But the moment came when Samuel did repent, even with tears. Why should that be so hard for us? Could the one who confronts us with our sin in today’s gospel be less understanding; less loving than Fr. Jeremy? Simply attend to this morning’s gospel and realize, it is Love, love incarnate who is saying to you at this moment: “Repent!” But if it really is Love Himself who is addressing you, then you are loved and if you are loved by Love Himself, and wish to repent, then you are as good as forgiven already—forgiven for everything! Think about that. It will make you want to laugh. Then let yourself laugh; laugh long and hard. Laugh, brothers and sisters, until you weep.

First Sunday of Lent

[Scripture Readings: Gen 2:7-9; 3:1-7; Rom 5:12-19; Mt 4:1-11]

We heard two beautiful stories from the Bible, one from the book of Genesis and the other from the Gospel of Matthew. Let me narrate another story.

In one creative drama workshop for senior high school students, the teacher gave the final exams. With ten participants, the group had to come up with a 30-minute skit depicting human misery in the contemporary world. They could select the plot and the setting given the theme of the play, improvise the props and the adlib the dialogue. The students were given a day to prepare and allot the roles to each member.

On the exam day at the school’s mini-auditorium, the teacher sat in a corner, while the students took the center stage for their presentation. After a brief introduction of the plot, the curtains opened. A live-in couple was on the brink of separation after protracted years of fighting. The man was unemployed, he was into gambling and drinking, and he physically abused his partner and their teenage son. The battered partner spent most of her years with him lamenting and eroding in her miserable life. After beating and verbally abusing her, he left the house and was determined to go for good.

In the meantime, the son who has witnessed the endless troubles at home lingered in his depression. He dropped out of school because of poor grades. He was into bad company and became addicted into drugs. In this scene, as the boy was hallucinating, one can hear a prompter as an inner voice urging him to kill himself. “Take extra drugs, Get a gun, or jump from the bridge!.” The prompter kept repeating these words and added, “after all, your life is a misery; better end your life.” The boy was already decided to jump from the bridge into the river. As he drove to the bridge, half-disillusioned, he got hit by a truck which badly injured him. His mother heard of the news and rushed to the hospital where her boy was brought. He was dying, but before his final breath, he kept saying, “I wanted to jump into the river and just die.” Then he died.

In the next scene, the mother was walking, deeply depressed, towards the bridge where the son was supposed to jump. She reviewed her life and it headed nowhere. Then the prompter on the left side of the stage again surfaced as an inner voice, saying, “Go, jump into the river. Your life is a total mess. There is no more sense and hope for your life.” Those words kept echoing in her mind and across the stage – and soon with a determination to end her miserable life, she stood at the edge of the bridge, and was about to jump into the river. With her left foot already out – suddenly, someone shouted, “Stop!…Cut!”

It was the teacher who called out for a break of thirty minutes. He told the students, “You have 5 minutes left for your skit. When you continue the story, see how you can depict a saving note to the tragedy.” So immediately, the students went into work. What

they did was to change the director, maintain the cast, and added another prompter to the scene. Two more characters were to play additional roles.

After the break, the members worked on their respective roles. There was the new director. As the curtains were raised anew, the story began where it left off. The woman was about to jump from the bridge, as prompter #1 echoed his words, “Go, jump. You are a hopeless case.” She was about to jump, when she heard the shout, “Stop, Mama!” Prompter no. 2 spoke and told her, “Before you jump, look to your right. There is hope.” She heard a boy calling, “Mama, stop!” The woman stopped as she looked to her right. She saw a boy running towards her. She thought twice and was touched. The boy then suddenly turned towards the other side of the bridge. She gazed towards that direction and there she saw a young mother about to jump too. She felt compassion for the boy and his mother. At once she ran towards the mother and grabbed her from falling into the river. She cried – this time not in tears of desperation, but out of joy in being of help to someone who was in greater need. She hugged the mother and the boy. She understood that after all, her life still had a meaning. Then the curtains closed. The teacher was proud of his students. They made it. He gave them all an excellent rating.

From the two parts of the play, the second one showed that no matter how miserable life is, there is hope. That is what the two stories from the Scriptures tell us today. Adam and Eve fell out of God’s grace and into the wiles of the Tempter. There seemed to be no hope for them. But then Christ comes into the scene. He too underwent temptations, but he made it over them. We are told that we too can make it. It is too hard to do it alone, but we need the Lord to make it. Temptations continue to remain actual and real in our lives, for the Tempter does not stop to win over us into his side. The objects of temptation could either be too delightful and attractive, or too miserable such that we want to take control of our life apart from God. The temptation is either to lead our life away from God or just take it. In such cases, we fall into the hands of the devil and fail. But if we listen to Christ and follow his leads, we can make it.

From the two parts of the play, the second one showed that no matter how miserable life is, there is hope. That is what the two stories from the Scriptures tell us today. Adam and Eve fell out of God’s grace and into the wiles of the Tempter. There seemed to be no hope for them. But then Christ comes into the scene. He too underwent temptations, but he made it over them. We are told that we too can make it. It is too hard to do it alone, but we need the Lord to make it. Temptations continue to remain actual and real in our lives, for the Tempter does not stop to win over us into his side. The objects of temptation could either be too delightful and attractive, or too miserable such that we want to take control of our life apart from God. The temptation is either to lead our life away from God or just take it. In such cases, we fall into the hands of the devil and fail. But if we listen to Christ and follow his leads, we can make it.

Never say that we are free from temptations or boast, “I am already immune to them.” Age, color, sex and creed do not guarantee total immunity from the test. Not even the place or the holy words can fully free us from the trials. Jesus was in the desert, then at the parapet of the temple, and lastly on a lofty mountain (Mt 4:1-11). All these were God’s favorite places of presences. But that was where the devil tempted him. Then the devil quoted holy words left and right to get Jesus to his side. However, Jesus stood fast because he was with God. The Spirit was with him and guided him. He let himself be guided by the Spirit.

Alexander Solzhenitzyn in his novel, The Gulag Archipelago, wrote, “the line dividing good and evil…cuts through the heart of every human being. This line moves and varies as time passes. In those with a heart filled with evil, there is a corner of good, and in the best heart there is an unacceptable pocket of evil.” Life remains a tug of war for Satan or God. The battle has been won by the Lord for us, but we need to affirm that we are with Him indeed. We too can make it.